I.

Let’s open with a riddle:

To cast away What cannot cut And sever words all tangled up

Don't try too hard to answer. This riddle embeds its solution according to a particular format, and though its rules are simple, without knowing them the text remains uninterpretable.

The solution goes something like this: to cast away is to rid. That which cannot cut is dull. And finally, words all tangled up is a riddle — rid and dull combined!

More explicitly, the first and second lines are each sub-riddles, whose monosyllabic solutions combine to form the poem's ultimate identity, which is restated in the final line. Ideally, the poem as a whole reflects something related to this identity. How does one solve a riddle? By casting aside dullness, and cutting through the webby obfuscations of language.

This elegant puzzle format is one of the lasting gifts of Antonia Barber’s Catkin, a picture book written for children in that strange twilight age between illiteracy and the middle-grade (more on this shortly). While only three such riddles feature in the story, the pattern is an invitation to create your own; a blueprint for those who would otherwise have no idea how to even begin composing a riddle. Step one: pick any two syllable word. (I have been working on a riddle for the word “soybean” for nearly a year. The fact that soy and been are bilingual conjugations of the same verb is very compelling.)

This kind of riddle is known as a phonetic charade, a fact I only learned after reaching out, in desperation, to some clever friends — it remains, as ever, difficult to google the shape of a thing, rather than the thing itself (and before you ask, yes, I tried AI, and it was clueless). These puzzles were apparently en vogue back in the Regency era, with Jane Austen being notoriously fond of them. Here’s one that she wrote:

When my first is a task to a young girl of spirit, And my second confines her to finish the piece, How hard is her fate! but how great is her merit If by taking my whole she effects her release!

The answer, apparently, is hemlock. Bleak!

As you can probably tell, Barber has made some age-appropriate changes to the puzzle’s conventions. She has removed the first, second, and whole markers that normally denote phoneme order, in favor of sticking to a three-line, sixteen-syllable poem. With all the detective work obsoleted by the new format’s predictability, it’s simple enough for a child to follow, and the rhyming, too, can be a boon to beginning readers.

Having gone on at length about the riddles, the time has come to admit that, despite their salience to the story's culmination, and my personal fondness for them, this is not a book whose focus is puzzles and riddlecraft. It tells, instead, a very simple story: that of a cat who descends into Hades to rescue his child companion. And by Hades, I of course mean Fairyland — but an interpretation thereof that does little to hide its similarities to the underworld of myth. Barber, an Englishwoman, sets her fairytale where Roman ghosts still roam.

Here is a brief summary: the titular Catkin is a tiny, runtish kitten born to a wise-woman’s cat. The wise-woman gifts him to a newborn girl, named Carrie. Catkin, the world’s most tolerant cat, becomes fast friends with little Carrie, and is rarely separated from her. One day, though, he wanders while she naps, and she is taken by the fairies that live under the hill.

The wise-woman tasks Catkin with retrieving her. He descends beneath the barrows, charms the fairy Lord and Lady, and bests them in a riddling competition — not, however, without speaking his own name, which grants them the power to compel him, though they are bound by the contest’s terms to free the girl. The fairies are at a loss: to relinquish both Carrie and Catkin would be too great a heartbreak, but if they keep the cat, the girl will mourn him, and they do not wish to harm her — for whom their love proves greater than their selfishness.

Catkin returns to the wise-woman one final time, requesting her adjudication. True to mythological form, she declares that Catkin and Carrie will go underground, to Fairyland, during the winter, and play above ground in the summer. Everyone is satisfied. Carrie’s parents embrace her, relieved, and the Lord and Lady bid them a temporary farewell.

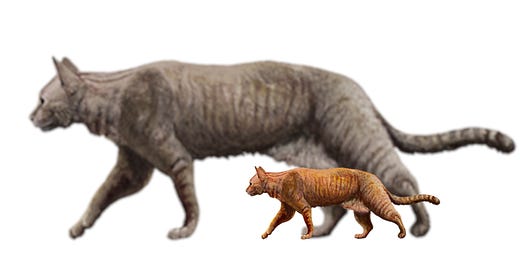

Original research interlude: Catkin is described as so small his tail is no bigger than the catkins hanging from the hazel trees. Assuming the hazel in question is Corylus avellana, his tail is at most 12 centimeters long. As the average cat tail length is about 30.5 centimeters, we can confidently assert that Catkin is less than 40% of a standard cat.

To understand what makes good children's fiction, it helps to understand where children's fiction commonly goes wrong. Most of it, of course, goes wrong by being opportunistic, contemptible dreck. Being short and often simple, children’s media is easy to mass-produce; the result is an aesthetically radioactive trash-scape of clipart pablum. (It will only get worse.)

P. J. Lynch's illustrations — for Catkin, and many books besides — are so lovely they make me forget we're living through an apocalypse. His process, gleaned from a smattering of interviews, entails dedicating an entire year to each book, including several months of preliminary ideation and sketching. Just hearing about this, for me, was soul-bleaching — if you have the misfortune of being steeped in the engagement-baiting world of rapid content generation, you may understand why such an intentional, solitary method feels like wizardry, or a forgotten science.

Catkin is 48 pages. My copy includes 17 full size illustrations, each of which, according to the illustrator, would have taken about two weeks to complete. There are many small inserts, and decorative borders for the text, not unlike those found in illuminated manuscripts. The paintings are made from models. In the illustrator blurb, Lynch states that he knew he “would have no shortage of models for Catkin or the old mother cat. My next door neighbor, Mrs. Tabiteau, owns about forty cats.” (Mrs. Tabby-teau!) Elsewhere, he admits that his mother posed as the wise-woman; in an interview about a different book, taken thirty years later, he describes modeling a character after his daughter. Time comes full circle.

The Underworld — pardon me, Fairyland — landscapes are earthy and dark, painted as though through an emerald’s swampy lens. Catkin and Carrie are the only sources of brightness underground. It reminds me, in spirit, of Arthur Rackham’s illustrations of The Goblin Market, a cautionary poem about goblin economies (don’t read anything into it!), whose young protagonist is likewise a beam in the murk.

Mind you, Catkin’s fairies are nowhere near as malevolent as those nasty goblins. Nor are they as tiny — though they are little, and drawn slightly smaller than something adult-shaped ought to be, such that next to Carrie their darkness and their scale is just wrong enough to produce an uncanny effect.

Which brings me to my next remark: children’s fiction also fails by being too tame. The aggressively sunny, puppy-drenched suburbia (or, occasionally, mixed-use walkable city) of standard kid’s media is intensely boring, unless it’s about trucks. Worse, it’s distant from the reality of childhood, which, while sheltered, is a time of great confusion: and behind that confusion, monsters.

Little annoys me more than the kind of book dedicated to “the beauty of imagination”, whose aim, I suppose, is to foster a creative spirit (already, we’ve breached lethal levels of condescension), which depicts a world that is wall-to-wall rainbows and bakeries. Let kids be frightened!

I’m not advocating for the insertion of toothy werewolves, or anything so explicit, into every story — ambiguity or absurdity will do the trick. A shadow, an eye through a peephole, a freaky-looking caterpillar; a dash of the sinister is the spice of life. Anecdotally, I’m still chasing the frisson I experienced, as a child, reading the “there’s a vug under the rug” page of Dr. Seuss’ There’s a Wocket in my Pocket.

Backtracking somewhat, I don’t mean to imply that the desirable opposite of tameness is horror, necessarily; horror is just one way of getting across the wideness of the world. Other stories will take other paths to weightiness: through the numinous, or the beautiful, or the inclusion of trucks, or the subtle suggestion of a great beyond, never fully realized in the text itself — or even through being crass and unexpected. This is all frustratingly difficult to quantify. You know it when you see it.

Catkin may only be a little bit eerie, but it is beautiful, and it takes itself with a solemnity not always granted to children’s books. Like The Hobbit — which by virtue of its self-seriousness manages to be both a comedy and an epic — this tale succeeds because it respects its audience, and their innocent (unsophisticated, to the snob) desire for a simple, heroic story; and one that does not subvert or deconstruct. Not that kids don’t love subversions — they love them with the enthusiasm of people just beginning to explore concept-space! They subvert things you would never think worthy of subversion! But such twists and contusions are, ultimately, only possible against a stable backdrop of conventions. Some-fable, some-when, has to do the thankless work of building the backdrop; Catkin does so wonderfully.

Now, you may have noticed a bit of sleight-of-hand: Catkin is a picture book, but I’ve been discussing it in the same breath as books that are both much longer (and pictureless) and much shorter than it. Well…

To understand what makes good children’s fiction, it helps to understand what a child is, and what the market thinks a child is. The industry seems to acknowledge, roughly, three vintages of child. There are consumers of “YA” (young adult) fiction, aged 13 to 18. There are consumers of “middle-grade” fiction, aged 8 to 12. And there are agents of chaos.

Researching what preceded middle grade, I compiled the following list of categories: first books, board books, sing-alongs, picture books, early readers, alphabet hermeneutics, fairy tales, educational fables, madcap amoral rollicks, concept books, chapter books, subhuman baby slop, compendiums of fine trucks. These all loosely correspond to developmental stages, though it’s unclear at times whether publishers intend to reference moral, educational, or emotional development. (Interestingly, middle-grade literature is associated with a third-person point of view, while YA is associated with a first-person point of view. I will not be unpacking that can of worms.)

Catkin sits awkwardly between categories. Some markets describe it as middle-grade, some as a picture book. Amazon lists its reading age as six to eight years old; an assessment that feels correct, as far as these things go.

According to certain Catholic traditions, seven is the age of reason — meaning, the age at which one becomes morally culpable. Circumventing discussions of sin and guilt, it marks the beginning of the capacity to weigh good and evil, to choose, and to be held accountable. I would like to call Catkin a book for the turning of the age of reason — its conclusion, after all, is all about decisions.

Two choices are made in the final act of Catkin (and there is a lesson to each). The first is straightforward: the heroic choice, in which Catkin grants the fairies the ability to bind him, at the same moment securing Carrie’s freedom. His carelessness lost her, but his sacrifice saves her. This act, though, leads to something like a stalemate; the game of riddles, which was supposed to resolve the conflict, has only created another moral quandary (although this time, the ball is in the fairies’ court). So it goes; the world iterates. There is no end, no final optimum. Only decisions behind decisions, until the reaper comes.

Of course, they choose to visit the wise-woman, because you can defer to a thinking human what cannot be deferred to an algorithm.

Catkin might not be a life-changing book, but it’s a testament to the crafts of riddling, writing, and illustration. It’s a charming reminder that lovely things can be made, and it’s brimming with the crooked wisdom of fairy tales. I’ve spent many years thinking about this book, and perhaps you can, too; or if not you, the children you know.

To quote an online reviewer, who convinced me I was not alone: “I am 27 years old and I still remember this book well and adore it and its lessons. It is touching and beautiful and I am certain that it has created in me a better and more thoughtful person than I would have been without it.”

In short, I recommend it. Thus ends my review of Catkin.

II.

Always desired While I grow long Endless as flowers, seasons, and songs

Here is the history of fairies in one sentence: pagan manifestations of otherness become nostalgic symbols of pre-industrial folkways become diminutive and oft glittery butterfly-winged females.

In slightly more than one sentence: the category “fairy” includes numerous European cryptids entities that share little more than their inhuman nature. While most often used to refer to cryptids entities from the British Isles, the word itself is Latin, coming from “the Fates”. This is suitably ominous — a typical fairy story includes magical illness, dancing to death, or kidnapped children.

Fairies are nature spirits. Fairies are reinterpretations of the Roman gods, who, though loosened in their grip, have yet to be forgotten. Fairies are the dead. Fairies are Scandinavian and Celtic memetic agents self-propagating via ballads. Fairies are ergot elves, the terrible pre-modern equivalent to DMT elves. Fairies are “of a middle nature betwixt man and angel”, unless they’re just demons. The fairies are generous, powerful, quick to anger, bound by indecipherable rules and customs, indifferent towards humans, and best avoided.

At some point, perhaps as early as the 17th century, the fear that fairies inspire begins to wane. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream may signal what is to come; his play is one of the first to depict fairies as beneficent little flower people. Come the Victorian era, believing in fairies is an escapist pastime. The world is hurtling into the future. The Cottingley Fairies are a series of hoax photographs in which wee garden fairies frolic with young girls.

Fairies are no longer perceived as dangerous. Fast forward again, and we have the popular fairies of today: Disney icons, be-winged Barbies and Bratz dolls, weird kid’s shows, and a saturation of the aesthetic that uncomfortably merges “pin-up” and “trying to sell this thing to children”. Saccharine, but also, creepy.

I propose that this evolution summarizes something about the ways that humans tend to perceive aliens. They are either scary, friendly, or “attempting to perform friendliness but falling into the uncanny valley”. (As for the tragic arc of fairies, specifically — you either die a villain or live long enough to see yourself become a plastic toy.)

So, which kind of fairies are present in Catkin?

Well, not the plastic ones. Scary, but not villainous; not friendly, but not unfriendly by default. Powerful, certainly. When Carrie is replaced by a changeling, her father’s first thought is to go to the fairies and plead with them: “I will show them our sadness and beg them to return our child.” Violence is never considered. Too mighty and strange to fight, yet there remains the hope of conversation.

I think this attitude, suspended between terror and openness, rooted in a deep capacity for sympathy, is, if not game theoretically optimal, a very noble one to take when dealing with inhuman entities. (Hypothetical inhuman entities. None are in the room right now.) And I think children can learn to be noble, long before they can learn to be strategic.

Catkin emphasizes, several times, the unearthly reasoning of the fairies. They steal Carrie not because they are cruel or callously selfish, but because they fundamentally do not understand the bond between a parent and a child. Maybe, as unchanging immortals, they don’t understand what a child even is; they are lonely underground, and yearn for company.

The wise-woman knows this, and communicates it, because she is an excellent intergalactic ambassador. And because their motivations aren’t malicious, they can be approached — though they are still gripped by their own logic, and will not hand back the child on human terms.

Fortunately, the humans and fairies do share a common fascination: riddles!

There is, in my opinion, something resolutely human about riddles. I would put them in the same class as tools, or fabric arts, in that they aren’t necessarily exclusive to this species, but represent an advantage, or pride, of humanity. Something important would be lost if there were no longer riddlers among us. Weird little word games, jesters in a box, toying with the gray areas of ontology and language. Most cultures have some kind of riddling tradition; to list them would be tedious.

When I was researching the riddle format created for Catkin, I considered calling it the “Barberism”, after its author. I found the wordplay with barbarism amusing — little seems to me more civilized than riddling. To engage with wits is a decadent alternative to engaging with fists.

One must not forget, though, that Catkin features a second type of inhumanoid: cats. Our hero, though he is aligned with human interests, must not be mistaken for one. Albeit sharing human goals, intelligence, and temperament, two important factors distinguish him from his bipedal patrons. Firstly, he is feline-shaped, and small enough to crawl through the burrows to Fairyland. Secondly, he is mute, except in the presence of the fairies.

Look, I’m not going to post the COMPUTERS MUST SHUT THE HELL UP meme. It should be obvious by now: Catkin is an allegory for an aligned artificial intelligence (necessarily silenced in human-world to preserve sanity and public order) sent on a crack mission to negotiate with an unaligned artificial intelligence regarding the stewardship of Carrie, who obviously represents —

Well, what do you think? Earth? Humankind? The eschaton? The essence of humanity, still in its toddler phase?

Time to solve this section's opening riddle. What is always desired? More. To grow long is to be tall. Finally, something as endless as the (decidedly finite) flowers, seasons, and songs is a mortal.

III.

Mouse-hunter Closer than a friend Wind-dancer at the bough's end

Here lies Catkin’s final riddle. Since this one is from the book, I won't spoil the answer; but you can solve it, can't you?

When I read Catkin, as a child, I understood the ending to be happy. Everyone shares! As an adult, it reads more like bitter compromise, an equilibrium between two irreconcilable factions. Happy, in that it has been reached without bloodshed. But as a parent, it is heart-wrenching.

Approximately once a week, the following sequence of events take place: I say “I need a break from these rascals!” -> I get a break from these rascals -> I spend the break mournfully yearning for those rascals. There is a magical window during early childhood when parents can account for every input into their child’s brain. You know every concept they know, every word, every image they’ve seen, every event that has transpired in their lives, and you witness it all churned up in their neural cauldron, broken and recombined in delightful ways. Like everything, that stage must end, and it shouldn’t be artificially prolonged, but while it lasts it’s a very profound form of intimacy. You can almost see the world through their eyes. You learn as they learn. To miss even a moment is deeply sad — no matter how badly you need some peace and quiet!

Consider, then, the resolution to Catkin: six continuous months of separation, every year. It’s almost too terrible to contemplate. Carrie, by my reckoning, looks to be no more than two years old. Referring to the developmental charts, six months at that age is the difference between, for example, “Uses two word sentences” and “Talks intelligently to self”.

Fairies, cats, and a third kind of alien: children. Doomed to become human, but not without passing through otherworldliness. Every milestone is a treasure. They probably can’t solve your riddles, but they speak naturally in their own. (A young girl in Piaget's The Child's Conception of the World describes “memory” as “a little square of skin, rather oval, and inside there are stories”. When you have few words, and few concepts to analogize your perceptions to, the world must seem like a series of riddles.)

Temporary separation, though, is not the greatest evil. When the fairies take Carrie, they leave behind a changeling, “a child made by enchantment”, whose sole purpose is to wither and die. Stepping outside the frame of the book, one theory I’ve heard regarding changeling myths is that they exist to comfort grieving parents, and explain away lost children. The fairies are called thieves, when really they’re (by a winding way) saviors; without the story of them, the child would be considered dead.

It’s difficult to tell when Catkin is set. Not medieval, not current. Like all good fairy tales, it floats in time, occurring on a farm that could have existed at any point between… I don’t know, 1870 and 1940. The most technologically modern item I spotted in the illustrations was a crumpled newspaper (great toy, for girl and cat alike); there seems to be no electricity, and the plow is pulled by horses. The fashion is ambiguous.

Taking my guesses at face value, we find that the child mortality rate in the United Kingdom was 26% in 1870. By 1940 it was at 7%, and steeply dropping. By today’s standards, these are both vertiginously high.

There are a couple of illustrations in Catkin depicting grief. The restrained pain of Carrie’s parents, shockingly visible; the theatrical, but no less broken, collapse of the fairy Lady. Suddenly, the bargain seems reasonable. Choices, trades, again and again. What’s one more?

Catkin ends with the following passage: “And from that day, all things went well for the good man and his wife. They lived in peace with Carrie and Catkin and the Little People, and the farm on the green hillside flourished.” That we could all be so lucky: to live and speak with aliens, to make peace, to choose well, to thrive, and to fight death, until we are no longer

Greater than some Higher than others Endless as sisters, daughters, and mothers.

Extremely rare ctrl post (and I'm sure that a plaintext/casual/direct, you know what I mean, post like this book review is even rarer) :0

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this: praise of children's literature, fairy history & lore, those that rid the dullness of life, magic everywhere, thoughtful sudden parellels to our world; I've never heard of this book before, but now I feel I must have it :)

A lovely, stimulating reflection. Thank you.

Allow me to commend to you Mervyn Peake's "Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor". Violence is offstage, but it's there. It's mostly about friendship (please don't read too much into it) and the illustrations are fabulous.

As for horror-stories (the good ones, anyway), I have written elsewhere:

"Horror stories are effective when they successfully undermine (or enable you plausibly to suspend) your belief in a narrowly rational universe. A staple of the genre is a character that is in denial about a horrific reality until it overtakes him. The genre is thus a rebuke to rationalist hubris and complacent materialism. It operates in a universe that is mysteriously open, liberating the reader or viewer from the oppression of one-dimensional rationalism (and its pecksniff enforcers)."